Articles

The Licensing Bill was ratified in the Commons yesterday (Tuesday 08 July) and should receive Royal Assent by the end of this week. It will be published as the Licensing Act 2003 next week.

Read the debate: http://www.publications.parliament.uk/pa/cm200203/cmhansrd/cm030708/debtext/30708-67.htm#30708-67_head0

There are some good speeches.

Sadly, this means the Joint Committee on Human Rights will not be able to further consider the Act. They did not meet last Monday, due to the fact that there were insufficient members present to constitute a quorum.

Featured live music in pubs and bars using any amplification at all remains illegal unless licensed, and still subject to potentially onerous conditions, although these may be partially alleviated via the small venues concession (see 'small venues - licence conditions concession' below). Unamplified live music in pubs and bars remains illegal unless licensed, but it does seem that any potentially onerous conditions that might otherwise relate to this category of live performance will be suspended where the small venues concession applies (also see below).

This is all the result of a last minute Government amendment of an amendment and is extremely complex. I would urge anyone with queries to contact Dominic Tambling at the Department for Culture on 020 7211 6351.

Clear Guidance for local authorities may militate against onerous conditions, but then again it may not. Local authorities tend to be very sure about what constitutes a 'necessary' condition. The only means to challenge a disputed condition - an appeal to magistrates, or judicial review - is costly and very time consuming, and likely to be beyond the means of smaller businesses.

Small venues - licence conditions concession This is my best shot at a summary - but contact the DCMS on the number above for clarification:

a.. In all cases, to qualify for the concession, the permitted capacity must be 200 or fewer and a premises licence must already be in force authorising 'music entertainment'.

b.. Music entertainment means the performance of live music or performance of dance. The amendment also makes a key distinction between places used primarily for the consumption of alcohol and those that are not:

Premises used primarily for the supply of alcohol for consumption on the premises This effectively means bars and pubs. The definition excludes restaurants, for example, libraries and hospitals, and any number of other potential venues for public performance.

If the bars or pubs qualify on the other criteria, and they provide performances of live amplified music, licence conditions relating to noise or the protection of children from harm will 'not have effect' initially. They would have effect, however, if problems or complaints led to a review of the licence. The suspension of noise and protection of harm conditions would apply whenever such premises are open and providing the live music. This could be round the clock. However, safety and crime and disorder conditions would apply at all times.

If such premises provide solely unamplified live music at any time between 8am and midnight, and they are not being used for the provision of any other description of regulated entertainment, then it seems any licence condition that would otherwise relate to the performance will be suspended (subject to review as above).

Everywhere else At other qualifying places such as restaurants, libraries, hospitals, public spaces, your front garden and so on, the wider unamplified concession applies, but if such places wish to provide amplified live music at any time, or unamplified music between midnight and 8am they will be subject to the full range of licence conditions. Local authorities would also seem to be able to impose any condition that did not relate directly to the provision of the music entertainment, but which they could argue was 'necessary' to achieve any of the four licensing objectives.

Noise conditions inconsistent Bars and pubs that open after midnight, particularly in towns and cities, are a major source of local residents' complaints, mostly about noisy people, but also noise breakout from within premises. And yet under the terms of the amendment they are exempt from noise conditions at any time (subject to review). By contrast, other places which may not sell any alcohol, and are not commonly associated with neighbour complaint, or anti-social behaviour, are subject to noise conditions after midnight.

What does it mean in practice? As now, where pubs and bars are concerned, local authorities will be empowered to impose any condition relating to the provision of live music, amplified or not, which they consider 'necessary' for public safety and crime and disorder. If local authorities argue, as they have consistently in the past, that because live music attracts more people than usual the installation of more toilets is necessary (public safety), or door supervisors are needed (crime and disorder), the only way for the licence applicant to challenge the conditions will be via appeal to the Magistrates court, or application for judicial review to the High Court. Both routes are are potentially costly and risky for the applicant, and likely to be beyond the means of smaller businesses. The delay between lodging an appeal and the hearing date can be months. And while licence conditions pertaining to regulate entertainment are in dispute the licensee must refrain from providing the entertainment, or implement the condition.

None of this palaver applies, of course, to activities that are not licensable - such as the provision of big screen broadcast entertainment.

In places not primarily used for the supply and consumption of alcohol and where completely unamplified live music is provided, the suspension of all licence conditions does represent a significant concession. In practice, however, it will benefit a relatively small proportion of performers.

Hamish Birchall

The Government has defeated the small events exemption proposed by Opposition Peers. The Lib Dem/Conservative alliance crumbled in the House of Lords this afternoon. The Government won by 145 votes to 75. The reason for the turnaround was that during behind the scenes horse trading late last night, the Government offered an outright exemption to morris dancing, and a marginal concession for unamplified live music. This appeared to satisfy the Lib Dems who decided to vote with the Government. The letters to all Peers from the Association of Chief Police Officers and the Local Government Association opposing the exemption were also influential.

There were powerful speeches in support of the exemption from Baroness Buscombe, who led for the Conservatives, and Lord Colwyn. Significantly, Lord Lester of Herne Hill, the guru of human rights law, also spoke out strongly against the Government position. He warned that it was, in his view, disproportionate interference with the right to freedom of expression under Article 10 of the European Convention. He contrasted the level of licensing control with the exemption for big screen entertainment (as did Lord Colwyn, and Baroness Buscombe). He speculated whether Lord McIntosh, the Government spokesman, would in a court of law still say that the Government's position was proportionate.

Lord McIntosh did not answer that point, but said the Government had made a commitment to review the new Licensing Act 6-12 months after the Transition Period - which means in about 2 years' time. He also announced that a 'live music forum' would be set up by the DCMS to encourage maximum take-up of live music under the new rules.

As a formality, the Commons will ratify the Government amendments (probably next Tuesday 08 July) and the Bill should receive Royal Assent by 17 July.

So what will the Bill mean for live music?

It is anyone's guess whether it really will lead to a significant increase in employment opportunities for MU members, and/or new venues allowing amateur performance. A positive outcome will depend to a great extent on the proactive efforts of musicians, performers unions, and the music industry, to make the best of the new law.

What has been achieved?

When the Bill was published it proposed a blanket licensing requirement for almost all public performance and much private performance. All performers were potentially liable to criminal prosecution unless taking all reasonable precautions to ensure venues were licensed for their performance.

Lobbying has led to:

a.. A complete exemption from any licensing requirement for regulated entertainment provided in a public place of religious worship.

b.. A similar exemption for garden fetes and similar functions, provided they are not for private gain.

c.. An exemption from licence fees for village halls and community premises, schools and sixth form colleges.

d.. An exemption for the performance of live music (amplified or unamplified) anywhere, if it is 'incidental' to other activities such as eating and drinking (but not dancing, or another licensable entertainment).

e.. An exemption from licence conditions (but NOT the licence itself) for unamplified live music in places such as bars, pubs, clubs, restaurants (i.e. where alcohol is sold for consumption on the premises) between 8am and midnight (subject to review, if, for example, this gives rise to problems for local residents).

f.. A limitation on licence conditions for amplified music in pubs, bars etc (subject to the same review procedure above), restricting those conditions to public safety, crime and disorder only.

g.. A complete exemption for morris dancing and similar, and any unamplified live music that is 'integral' to the performance.

h.. An exemption from possible criminal prosecution for ordinary performers playing in unlicensed premises or at unlicensed events. Now only those responsible for organising such a performance are liable, this includes a bandleader or possibly a member of a band who brings an instrument for another player to use. There remains a 'due diligence' defence, however (taking all reasonable precautions first etc).

i.. A clarification that at private events, where musicians are directly engaged by those putting on the event, this no longer triggers licensing (however there remains an ambiguity that if entertainment agents are engaged to provide the band, this does fall within the licensing regime).

In spite of all this, the Bill does mean 'none in a bar' is the starting point of the new licensing regime. Any public performance of live music provided to attract custom or make a profit, amplified or not, whether by one musician or more, is illegal unless licensed (other than in public places of religious worship or garden fetes etc). In the opinion of leading human rights lawyers, like Lord Lester, this remains a disproportionate interference with the right to freedom of expression - whatever the Government may say about how easy or cheap it is to get the licence. The point being that there is and never has been evidence of a problem sufficient to justify such interference. Why add new rules where there are enough already?

The Bill for the first time extends entertainment licensing across all private members clubs, and registered members clubs. It also captures private events, such as charity concerts, if they seek to make a profit - even for a good cause.

The Bill creates a new category of offence for the provision of unlicensed 'entertainment facilities', which would include musical instruments provided to members of the public for the purpose of entertaining themselves, let alone an audience.

However, the 'incidental' exemption could prove to be quite powerful, but that will depend to a great extent on how local authorities choose to interpret the provision. The Guidance that will accompany the Bill may become particularly important on that point, and others.

This is by no means an exhaustive analysis of the Bill's provisions for live music, but should serve as a summary.

My sincere thanks to all who have kept pace with these developments and lobbied their MPs, Peers and the press.

Hamish Birchal - MU Advisor

Last Thursday, 03 April, the Commons Licensing Bill Committee concluded its debate of Schedule 1 that deals with definitions and exemptions for 'regulated entertainment' and 'entertainment facilities'. As predicted, Culture Minister Kim Howells and fellow Labour MPs on the Committee have voted to remove the Opposition Peers' exemption for educational establishments (paragraph 14). The Committee now moves on to other parts of the Bill, a process that must be finished by 20 May.

Given that the Government can simply reverse anything the Lords have changed, people understandably ask: 'what is the point of continuing to lobby MPs?'. This circular attempts to explain why it is not just important but essential to continue lobbying MPs, particularly Labour and Liberal Democrat MPs. Part of the reason is that the show-down, if you like, is yet to come. The other part concerns Parliamentary process, and how this can work in our favour with the Licensing Bill.

Schedule 1 will not be debated again until the entire Bill as amended by the Committee receives its Report/3rd Reading in the Commons. Unlike the Lords, Report and 3rd Reading debates will be on the same day, back to back. The precise date has yet to be fixed, but is likely to be some time in the fortnight commencing 2nd June. Further amendments can be put at Report stage, but these will be limited in number, and for that reason carefully chosen. More on that later.

It suprised me that a Commons Committee of only 16 MPs can change an entire Bill, but that is the way the process works. The Committee votes on amendments of their own, and these can be put down by any of the MPs on the Committee. The composition of the Committee reflects the proportion of MPs by Party: 10 Labour, 4 Conservative, and 2 Lib Dem. So if the Labour MPs vote with the Whip, i.e. they toe the Party line, then the Government can do what it likes to the Bill at this stage. That is what is happening at the moment.

However, if Committee amendments change or reverse amendments that were introduced by the House of Lords, that has to be approved by the Lords. So once the Bill completes Report/3rd Reading, it goes back to the Lords. At that point the Lords may reintroduce Clauses they originally inserted but which were subsequently removed in the Commons, or amend any or all of the Clauses they first amended, but which were changed again by the Commons. The Bill must then return to the Commons, the idea being that the Bill cannot become law until its content is agreed by both Houses.

The Conservatives have promised to revisit the small events exemption when the Bill goes back to the Lords. Provided the Lib Dems support the Conservatives (as they did when that particular amendment was voted through on 11 March), there is a serious risk that the Government's timetable will be delayed. The Conservatives and Liberal Democrat Peers combined outnumber the Government in the Lords. Opposition Lords could therefore start a game of 'ping pong' between the two Houses.

Now comes the crucial bit: the Government cannot force the Bill through using the Parliament Act. For some reason I don't fully understand, Bills that have been introduced in the Lords are immune from the Parliament Act - only Bills introduced in the Commons can be forced through by that means. The Government are extremely anxious for the Bill to receive Royal Assent by July. So it is entirely possible that, faced with a solid opposition in the Lords, they might make a concession on the entertainment licensing side. So we are definitely still in with a chance of the Lords amendments on small events and educational establishments, or variations of these amendments.

It is also possible that a version of these amendments will be introduced by Opposition MPs during Report/3rd Reading in the Commons, before the Bill goes back to the Lords. Not all Labour MPs are against the ideas in principle by any means: indeed both Bob Blizzard and Jim Knight have argued in favour of some kind of exemption.

Public pressure will determine to a great extent whether Labour MPs are receptive to the arguments for a 'de minimis' exemption permitting a limited amount of entertainment/live music before entertainment licensing kicks in. That is why it is extremely important for the MU and musicians to keep lobbying and talking to their constituency MPs.

Hamish Birchall

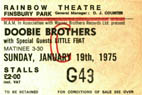

I must admit to being somewhat gobsmacked when this album - reduced from original 1975 12" rolling table size to envelope friendly CD proportions courtesy of a biz aimed howitzer better known to us as a CD burner - slid out of a Christmas card.

But what could be so potent about a home burned copy of a 1975 label sampler that retailed back then at the giveaway price of 59p, slightly less than 20% of a full price release if memory survives. It wasn't the price, tho', imagine any label, any major label, issuing a full album of its major signings at less than the price of a single in 2003. Indeed a tour promo set, which in essence is what this was, would most likely be sprinkled with unreleased / left over tracks and racked at full price having been given dubious collectors status.

No, what hit home was the range of artists on the disc. Remember, this was a tour promo, the acts featured were on tour in the UK together. Imagine; Little Feat, hip, funky and hot. The Doobie Brothers, a pre MacDonald cocktail of hard rock and gospel washed acoustic musings. Graham Central Station, a hard funk amalgam built around Sly And The Family Stone's erstwhile innovative bassman Larry Graham. Tower Of Power, kinda Chicago with balls; funky and jazzy with attitude and charisma. Montrose, shiny metal before the genre was left out to rust and Bonaroo, white bread west coast harmony pop make weights. Think about it; a fistful of genres that spell confusion to 21st century marketeers who could never imagine anyone sitting through Little Feat's Oh Atlanta, Montrose's Bad Motor Scooter and Tower Of Power's Don't Change Horses and yet that's exactly how tracks 3 to 5 run. And remember this is pre CD; no programming out the bummers, that meant getting up and physically making the change inn an age when listening was a more, shall we say, mellow, occupation.

Now I know that some of you may wonder what the hell I'm going on about pointing out quite rightly that such collections as Back To Mine often feature such juxtapositions as Captain Beefheart and St. Germain or King Tubby, but remember that these are celebrity enhancement collections, not mainstream promotions. And they're £12 or more!

My point is simply this, nigh on 30 years back music was allowed to breathe, to coexist, cross pollinate. Audiences were credited with the intelligence to make choices, not assigned a style ghetto. And today those of us that were infected by such callous disregard for the disciplines since learned by record companies, marketing, PR, test marketing and more, are forced to rally round such outposts as Netrhythms where our affliction, known as musicismusic, finds sympathetic treatment. Mind I did pick up a magazine called the Word, recently and I can't for the life of me work out whether it's a beacon of hope, or the final cry of the similarly infected.

Little Feat

Doobie Brothers

Tower Of Power

Montrose

Graham Central Station

Steve Morris

The MU today held a press conference to address accusations by Kim Howells that the Union is leading objectors to the Bill in a 'pernicious lying campaign'. Two independent lawyers were present, neither representing the Union. Both have studied the Bill closely. Both share MU concerns about the scope of the Bill's definitions and the implications for live music, particularly folk and jazz. They were invited as representatives of the legal profession with particular concerns about the Licensing Bill: Chris Hepher, an expert in licensing law, with 20 years experience working in the PEL and liquor licensing field; and Robin Bynoe, a music business solicitor and amateur musician who assisted in drafting some of the amendments during the Bill's Committee stage (which is now over - the next 'Report Stage' should take place within the next 3-4 weeks).

Journalists from The Times, Daily Telegraph and The Stage attended. Interestingly, the Department for Culture sent along an 'observer' who took copious notes. She also provided us with a statement from Howells who maintained the Party line: the MU are scaremongers, and their claims about the Bill are 'fantasy'. Both the lawyers, on the other hand, completely endorsed our claims.

The DCMS have now provided a comprehensive commentary in response to MU concerns, and the concerns of other groups (see below). As a statement of intent, some of it is welcome (i.e. no wish to licence private events where musicians charge a fee etc). However, this intent is not - yet - reflected in the words of the Bill. You may also notice some rather slippery justifications.

I apologise for the amount of information, but I think it is better that you have the complete document rather than edited sections. If you can find time to read it all, please keep a few points in mind, particularly in relation to the safety and noise justifications for licensing:

a.. This Bill criminalises almost any public music-making - unless licensed - however small in scale.

b.. Many categories of currently exempt private performance are also caught - again, however small in scale.

c.. No licensing regime that criminalises an activity will be 'light touch', however cheap the fees.

d.. The exemption for broadcast entertainment means that premises (any place, not just pubs) can install multiple widescreens and powerful sound systems without a licence under this Bill.

e.. The Association of Chief Police Officers (ACPO) objected to this exemption on crime and disorder grounds. Tackling crime was the government's main selling point of the Bill.

f.. Under the entertainment facilities section of Schedule 1 (para 3) there is no requirement for an audience to be present (READ SCHEDULE 1) - this applies to bell ringing, music shops, rehearsal rooms and music studios. They are all facilities for music making, provided for the public 'for the purpose, or purposes that include the purpose, of being entertained.'

g.. The Joint Committee on Human Rights report on the Bill said the government had provided no justification for criminalising all musicians who perform without first checking that a premises is licensed. They commented that the explanation offered was an attempt 'to pull the Bill up by its own bootstraps'.

h.. In England, as in Scotland, there is nothing stopping licensing justices imposing noise or safety conditions on the grant of liquor licences. Licensing justices continue to use this power in spite of the fact that there is guidance (without statutory force) advising against the practice. Setting a 'safe capacity' in this manner is relatively common in London and Birmingham. Otherwise, all health and safety and noise legislation in Scotland is exactly the same as in England - it is shared legislation, unlike licensing which is separate.

i.. The case law precedent from 1899 determined that where two (or possibly more) pub customers made music for their own amusement on a pub piano, on a weekly basis, unpaid - this was exempt from licensing as public entertainment. The Licensing Bill would not only render this activity illegal unless licensed, but also the provision the piano is itself a criminal offence without a licence!

* * *

DCMS Comment

REGULATION OF ENTERTAINMENT UNDER THE LICENSING BILL

Contents

Introduction

1. The Licensing Bill

2. The provision of regulated entertainment under the Bill

3. Entertainment in places where alcohol is sold

4. Entertainment in community centres and village and parish halls

5. Entertainment in schools and colleges

6. Entertainment in private homes and gardens

7. Entertainment in churches, synagogues, mosques and other places of worship

8. Entertainment in sports clubs

9. Music and dance studios

10. Music shops and recording and broadcasting studios

11. Why licence entertainment

12. Folk music and traditional activities such as Morris dancing, wassailing etc

13. Clowns, story-tellers, magicians, children's entertainers, stand-up comedians

14. Carol singing

15. Church bell ringing

16. Spontaneous singing

17. Rehearsing or practising

18. Music lessons

19. Exemptions for broadcast entertainment and incidental music

20. The Bill's compliance with the European Convention on Human Rights

21. Entertainment events held to raise money for charity

22. Licensing of live music in Scotland

23. The new licensing regime and existing laws

24. Penalties for carrying out licensable activities without a licence

Introduction

Many individuals and organisation have expressed serious concerns about the effect that the Licensing Bill will have on live music, and other forms of entertainment. Many of the fears that exist are unfortunately based on misinterpretations of its provisions. The Bill has been drafted, as all Bills are, by Parliamentary Counsel following instructions from the Government. We have considered the alternative interpretations that have been put to us but have concluded that they are incorrect.

This paper seeks to address the issues raised in relation to entertainment and correct any misconceptions. It begins with a short explanation of what the Bill does say in relation to entertainment and what this means in practical terms. It then deals with a number of issues relating to particular entertainment activities and some more general points. The paper gives examples where possible but it must be borne in mind that it is always possible to think up a case where one parameter has changed that might alter the position in regard to the new licensing regime. The information provided in the first part of this paper should, however, make it relatively simple to work out whether or not a particular activity is licensable.

1. The Licensing Bill

1.1 The Government believes that the Licensing Bill will provide a new licensing regime that increases the opportunities for musicians and other performers. We believe that these reforms will give the arts in England a new lease of life rather than sounding its death knell as some are suggesting. The Department for Culture, Media and Sport is of course also responsible for the arts and we continue to have both performers and their audiences at the forefront of our minds as we take the Licensing Bill through Parliament.

1.2 Under the new licensing regime there will be no public entertainment licence: it will completely disappear. Permission to sell alcohol, provide entertainment for the public, stage a play, show a film or provide late night refreshment will be integrated into a single licence - the "premises licence", cutting significant amounts of red tape at a stroke. Under the new regime, any public house will need to obtain permission to sell alcohol for consumption on those premises and will be free to apply simultaneously for permission to put on music or dancing or similar entertainment whenever desired. The fee for such a premises licence will be no different whether the pub simply seeks permission to sell alcohol or if it decides to apply for additional permissions, for example to provide entertainment. The existing cost and bureaucracy, which acts as a deterrent in many cases, will be removed.

1.3 The position now is that many pubs are wary of obtaining a separate public entertainment licence because the costs can be prohibitive in some local authority areas. Subject to continuing discussions with stakeholders, any variation in fees will more likely relate to the capacity of the venue so that smaller venues pay less than large ones. The fees will also be set centrally by the Secretary of State to eradicate the wide and sometimes unjustified inconsistencies that presently exist. The Regulatory Impact Assessment, which accompanies the Bill, estimates that the one-off cost of applying for a premises licence would be between £100 and £500, with an annual charge of between £50 and £150.

1.4 Guidance will also be issued by the Secretary of State to licensing authorities when the Bill is passed that will make it clear that any conditions attached to licences must be tailored to the needs of the particular premises and must be necessary for promoting the licensing objectives. This should prevent the issuing of swathes of unnecessary and irrelevant conditions, which may prevent licensees applying to hold public entertainment events.

2. The provision of regulated entertainment under the Bill

2.1 The Bill considers entertainment in terms of the provision of regulated entertainment. Only entertainment, or entertainment facilities, that come within this definition will be licensable. For the most part this paper uses "entertainment" as a short hand for entertainment and entertainment facilities.

2.2 In order to be regulated entertainment, the entertainment must satisfy two conditions. The first of these is that it must be provided:

(a) to any extent for the public or

(b) exclusively for members of a qualifying club for members and their guests or

(c) where (a) and (b) do not apply, for consideration and with a view to profit.

2.3 The Bill further says that entertainment is only to be regarded as provided for consideration if any charge:

(a) is made by or on behalf of any person concerned in the organisation of the entertainment; and

(b) is paid by or on behalf of some or all of the persons for whom that entertainment is provided.

2.4 This means that all performances will be licensable if the public are admitted. If they are not, licences will generally only be needed if those attending are charged to attend, with the aim of making a profit (including raising funds for charity). Payment to an agent or to a band to appear at a private wedding, for example, would not result in a requirement for a licence unless the guests are charged to attend with a view to profit. We are not aware of many weddings being staged in order to secure profit from invited guests. The reference to "on behalf of" in paragraph 2.3 above implies agency, that is someone buying a ticket on someone else's behalf with their money and not his own. A licence would not therefore be required where the host of a private party pays for entertainment that is subsequently enjoyed by his guests or where a company that pays for entertainment at its in-house Christmas party for staff, where neither the guests nor the staff pay for tickets to attend the event at a level that would generate profit for the organiser.

2.5 Performances at places such as hospitals and old people's homes would also not be licensable unless the public were able to attend, or a charge was made to those inhabitants or patients who attended with a view to do more than cover costs.

2.6 The second condition that must be satisfied in order for entertainment to be regulated is that the premises on which the entertainment is provided are made available for the purpose of enabling the entertainment to take place.

2.7 The descriptions of entertainment covered by the Bill are:

· the performance of a play,

· an exhibition of a film,

· an indoor sporting event,

· a boxing or wrestling entertainment,

· a performance of live music,

· any playing of recorded music,

· a performance of dance

· or entertainment of a similar description to any of these, where the entertainment takes place in the presence of an audience and is provided for the purpose of entertaining that audience.

2.8 Entertainment facilities are defined by the Bill as facilities for enabling persons to take part in music making, dancing or similar entertainment, for the purpose of being entertained. An antique piano in a pub that was only provided for decorative effect would not give rise to the need for a licence. And a licence would not be required if the pub operator did not allow the public to play it. A licence would only be required if it was used to entertain people at the premises or by people on the premises to entertain themselves.

3. Entertainment in places where alcohol is sold

3.1 It has been claimed that "110,000 on-licensed premises in England and Wales would lose their automatic right to allow one or two musicians to work. A form of this limited exemption from licensing control dates back to at least 1899."

3.2 This point is disingenuous. In 1899, the courts held that impromptu performances by customers were not licensable, but performances given by a customer or any musician "for a consideration" were licensable. The Report of the Royal Commission on Licensing (England and Wales) 1929 - 1931 (paragraph 249) confirmed this interpretation of the law. Working musicians were therefore not exempted as claimed. The "two in a bar rule" was introduced by the Licensing Act 1964. The Bill does abolish the "two in a bar rule" but introduces new arrangements whereby any pub may obtain permission to stage live musical events at no extra cost when obtaining permission to sell alcohol.

3.3 Under existing legislation all public performances of music in licensed premises are licensable. The only exemption is provided by the "two in a bar" rule, which allows two musicians or less to perform without a public entertainment licence when a Justices' Licence is held.

3.4 We are abolishing the two in a bar rule for two very good reasons. First of all, the effect of the rule is very restrictive - it restricts drastically the forms of entertainment that may be carried out. Only entertainment consisting of one or two performers of live music is exempt. Anything beyond that - including the performers combining live music with sound recording - requires an additional licence. The perverse effect of the rule is that many types of music and other forms of entertainment are discouraged by reliance on the existence of the rule. Furthermore, this means that the range of cultural experience available to the general public is narrowed severely.

3.5 Secondly, the rule is anachronistic. It is quite possible for a single performer using amplified equipment to give rise to considerably greater nuisance than four or even more entertainers performing acoustically. The Government simply does not accept that live music in pubs is never a source of disturbance. The Institute of Acoustics lists "amplified and non-amplified music, singing and speech sourced from inside the premises" as a principle source of noise disturbance from pubs, clubs and other similar premises. It is equally the case that the public safety issues that the Bill addresses can arise where there are one or only two performers. It is therefore important that the likely risks are considered and proportionate steps taken to address them if necessary.

3.6 What we are putting in place is a simple, cheap and streamlined licensing system that should encourage - if industry makes full use of the reforms - a huge opening up of the opportunities for performing all sorts of regulated entertainment.

3.7 The Musician's Union proposed in February 1998 that every venue currently covered by a Justices' Licence (to permit the sale of alcohol) that wished to engage live performers should be required to have an entertainment licence. Although there will of course be no entertainment licence as such under the new regime, only a permission to provide entertainment on the premises licence, this is the model that we have followed. The Musician's Union also suggested that the playing of recorded music should be treated in the same way. Recorded music is a licensable activity under the Bill but there is an exemption for incidental music that is discussed later in this paper.

4. Entertainment in community centres and village and parish halls.

4.1 Under the present system live music is licensable in community centres and village and parish halls. Outside Greater London these venues do however enjoy an exemption from fees. Under the Licensing Bill the cost of a premises licence is likely to be negligible for these places and, taken with the savings, which will be made in other areas such as liquor licensing, the result will be a net reduction in costs for these venues. The Bill will give the Secretary of State powers to waive or reduce fees if she thinks it appropriate. During the passage of the Licensing Bill through Committee in the House of Lords, the Government gave an undertaking that it was considering very carefully the case for such an exemption.

4.2 These halls will also be able to benefit from a more informal system of permitted temporary activities that the Licensing Bill will introduce. Anyone can notify up to five of these per year, or fifty if they are a personal licence holder. Each event can last up to 72 hours and up to five events can take place at one premises in any year where less than 500 people attend. These permitted temporary activities will require a simple notification to the licensing authority and the police and a small fee of around £20.

5. Entertainment in schools and colleges 5.1 Entertainment provided by a school or college to which the public are admitted is currently licensable and will continue to be licensable under the new regime. This is mainly because the public safety issues involved would be the same as for any other venue.

5.2 A concert or other performance in a school or college which takes place for parents and students without payment will, however, be exempt from the licensing regime. Similarly, if the school charges parents and students but does so only to cover its costs, no licence would be required. This would mean that the school nativity play in the form that we all know would not need a licence.

5.3 Any performance of music, dancing, etc that is being performed for students as part of their education would be exempt as it would not be provided for the purpose of entertainment.

6. Entertainment in private homes and gardens

6.1 The Private Places of Entertainment (Licensing) Act 1967 already enables local authorities to licence many private events that are promoted for private gain. The only places otherwise exempt under the 1967 Act are premises licensed for other purposes. The Licensing Bill draws together these varied permissions into a single scheme that is clearer and easier for everyone to understand and use.

6.2 However, any performances of live music that take place in private homes and gardens for private parties and weddings will not be licensable unless the host takes the unusual step of charging the guests to attend with a view to making profit.

6.3 The Bill does nothing to affect what people are entitled to do in their own homes unless the public are admitted or guests are charged with a view to profit rather than to simply cover costs.

7. Entertainment in churches, synagogues, mosques and other places of worship

7.1 The Government has been at pains to ensure that appropriate exemptions may be enjoyed by any faith when they are engaged in worship or any form of religious meeting.

7.2 Outside London current public entertainment licensing law exempts music in "a place of public religious worship or performed as an incident of a religious meeting or service." "A place of public worship" means only a place of public religious worship that belongs to the Church of England or to the Church in Wales or which is for the time being certified as required by law as a place of religious worship. The Licensing Bill maintains an exemption for any entertainment for the purposes of, or incidental to, a religious meeting or service.

7.3 As currently drafted the Licensing Bill would remove the exemption that churches outside London currently enjoy in relation to music that is not performed as part of a religious service. - for example , a secular concert performed at churches that might range in size from the small local parish church right up to St Paul's Cathedral. However, the Government understands the breadth and depth of feeling that surrounds the issue.

7.4 Both Baroness Blackstone and Kim Howells have made it clear that the Government will amend the Bill to avoid placing unnecessary burdens on churches. DCMS is discussing possible solutions with church organisations and suitable amendments will be tabled for consideration at Report stage in the House of Lords.

8. Entertainment in sports clubs.

8.1 Contrary to some claims, sports clubs do not enjoy any exemptions for the provision of entertainment to which the public are admitted. In addition, if a club is selling alcohol as a registered members club for its members and their guests, it needs a certificate of suitability from the local authority for entertainment provided after 11pm and a special hours certificate from the magistrates' court. If they are currently holding activities without licences it will be for other reasons such as that they are private events.

9. Music and dance studios.

9.1 The Licensing Bill will not result in the licensing of performances in a rehearsal studio or broadcasting studio for the simple reason that no audience would be present. A licence would only be required if the equipment in the studio is being used to provide entertainment to the public and as rehearsal studios do not generally provide entertainment or the facilities for people to take part in entertainment there is no requirement for a licence. However, if a dress rehearsal is provided for the public an authorisation will be required. A broadcasting studio recording a programme without an audience is similarly exempt.

10. Music shops and recording and broadcasting studios

10.1 With regard to a music shop, if a customer wishes to test a new musical instrument, for example, there would be no requirement for a licence. The playing of the instrument in the shop is for the purpose of demonstrating and selling the instrument, and not for the purpose of entertaining the potential purchaser.

10.2 Performances in a rehearsal studio or broadcasting studio are not licensable where there is no audience present. Entertainment facilities at such studios only give rise to a requirement for a licence if the means provided for making music are provided for enabling persons to take part in an entertainment. Rehearsal studios are not providing an entertainment or providing facilities for people to take part in an entertainment. A broadcasting studio recording a programme without an audience is similarly exempt because it does not charge the musicians for the facilities. On the contrary, it pays them.

11. Why licence entertainment

11.1 The Government requires certain types of entertainment to be licensed because they raise issues of public safety, nuisance and sometimes crime. The Government does, however, recognise that the licensing system should be able to take into account the nature of the entertainment and treat it accordingly. Under the present system local authorities sometimes attach swathes of standard conditions to entertainment licences whether or not they are needed. This will not be possible under the new licensing regime. Major venues staging rock bands would therefore be the subject of more restrictive conditions than a small pub or club that puts on unamplified live music.

11.2 The Government does not accept that certain types of music, for example acoustic, are never "noisy" or never raise public safety issues and should therefore be excluded from the licensing regime. If music is to be performed for the public at a premises, then the licensing authority should have the power on receiving representations to impose necessary and proportionate conditions in order to protect residents and customers.

11.3 Nor does the Government accept that existing health and safety and noise legislation provides sufficient safeguards where premises are used for entertainment. Health and safety assessments relate to premises in normal use. Their use for entertainment often gives rise to particular issues, for example:

a.. Temporary cabling and staging

b.. Blocking of fire exits

c.. Unusual distribution of people in the premises

d.. Certain aspects of crowd behaviour

e.. Unusual noise disturbance

It is to address these and similar issues that public entertainment has been and continues to be a licensable activity.

12. Folk music and traditional activities such as Morris dancing, wassailing etc.

12.1 There is no reason why any of these activities should be adversely affected, as at present any performance that involves more than two musicians or dancers in a single session would require a licence. Under the new regime licences for music and dancing can be obtained for any premises where an application to sell alcohol is made at the same time for no additional cost.

12.2 As detailed above, centrally set licence fees and the control of conditions imposed by licensing authorities will remove the deterrent of high charges for licences and allow these activities to flourish. In addition, spontaneous singing and dancing would not be caught.

12.3 Unfortunately, music is also sometimes associated with drugs culture and related crime. This is not just true of nightclubs. The 16th Annual Brecon Jazz Festival resulted in 90 arrests for controlled drugs offences and 23 people were taken into custody for public order disturbances.

13. Clowns, story-tellers, magicians, children's entertainers, stand-up comedians

13.1 These entertainments would not of themselves be licensable. They might however require a licence if, for instance, a comedian played the guitar and sang a number of songs as part of his act and the entertainment fulfilled the other conditions of a licensable activity.

13.2 Even if these performers activities were licensable because, for example, a guitar was played as part of the performance, no licence would be required for performances that took place in private homes or gardens for private parties unless the host took the unusual step of charging the guests to attend with a view to making profit. The same would apply to performances at children's or old people's homes. However, if the entertainment takes place at a venue to which the general public are admitted, or if the audience was charged, with a view to profit, to attend, a licence would be required.

14. Carol Singing

14.1 Carol singers going from door to door, or just deciding to sing in a particular place, or even turning up unannounced in a pub and singing - whether collecting for charity or not - would not be providing regulated entertainment, just as drinkers in a public house who suddenly decided to start singing carols would not be licensable. However, where a place such as a shopping centre arranges for a group of singers to sing carols this will be the same as their arranging any performance of live music. It will be the provision of regulated entertainment and will need to be provided under the authorisation of a premises licence or temporary event notice.

14.2 The position for carol singers within London would be no different under the new regime. Outside London, carol singers who perform organised events inside a building would continue to be licensed - they are currently licensed under the Local Government (Miscellaneous Provisions) Act 1982. However, carol singers who perform organised events in the open air would require a licence for the first time once the Bill comes into force. However, it is not unreasonable to expect that a shopping centre, railway station or similar premises obtain a premises licence or temporary permission to enable such entertainment to take place.

15. Church bell ringing

15.1 Church bell ringing would not be licensable. First, if the bell ringing were incidental to a church service it would be exempt. Secondly, if it is undertaken as a hobby or for fun, it would not be licensable because there would be no audience present on the premises and finally, the bells would not be licensable as an "entertainment facility" because the church would not charge the bell ringers for the use of the facilities. However, if an organised bell ringing event takes place for the public that would be licensable.

16. Spontaneous singing

16.1 Section 2 above sets out what is regulated entertainment for the purposes of the Bill. Any spontaneous singing, for example of "Happy Birthday" would not be licensable.

16.2 This is not explicitly stated in the Bill because it does not need to be. Legislation sets out definitions of the activities that need to be licensed and any exemptions that might apply. It does not provide exhaustive lists of the activities that are not licensable. This is unnecessary. An activity is either within the scope of the definition or exemption but if it is not it is not covered by the provisions of the Bill. The Government is not going to change the form of Government Bills that has been used for hundreds of years just because the Musician's Union disapprove of it.

16.3 Contrary to some suggestions, a postman whistling on his round would not require a licence.

17. Rehearsing or practising

17.1 Practice or rehearsal of any form of entertainment would not be licensable unless the public were allowed to attend or a charge was made for a private audience. A dress rehearsal to which the public were admitted would be licensable.

18. Music lessons

18.1 Music teachers will also not be licensable because there is no public performance and the playing of music in this context is not for the purpose of entertaining the students but for the purpose of educating them. An end of term concert given by the pupils of a particular teacher would also be exempt so long as the invitation to attend was only open to family and friends and the general public were not invited, unless a charge was made to attend with a view to a profit (ie to cover more than costs).

19. Exemptions for broadcast entertainment and incidental music

19.1 Broadcast entertainment on satellite or terrestrial T.V will be exempt from the licensing regime. This is for a number of reasons, including that the Bill is deregulatory and does not require the licensing of any forms of entertainment that are not currently licensable. It is also the case that no professional bodies responsible for public safety have approached the Government arguing that it is necessary to licence such activities under the Bill.

19.2 In the Bill we have identified entertainments that need to be licensed in their own right. For example, music and dancing because of, among other things, noise and drugs culture and late night refreshment because of disturbance. Watching television - which almost every citizen does every day of their lives - does not in itself give rise to the need for licensing.

19.3 The Bill also contains an exemption for the playing of recorded music that is incidental to other activities that are not of themselves entertainment. Jukeboxes in a pub would not therefore need to be included on a premises licence, unless, for instance, a dance floor was also provided. The reasons for this exemption are similar to that of broadcast television that is that the playing of incidental recorded music does not of itself give rise to issues that require it to be licensed. A DJ playing to a public audience would, however, be licensable.

20. The Bill's compliance with the European Convention on Human Rights

20.1 Baroness Blackstone has made a statement under section 19(1)(a) of the Human Rights Act 1998, saying that she is satisfied that the provisions of the Licensing Bill are compatible with the European Convention on Human Rights.

20.2 The Joint Committee on Human Rights has written to the Department for Culture, Media and Sport for further information in relation to two specific matters. The Department has replied and awaits the Committee's response.

20.3 The right of freedom of expression has to be balanced in a sensible and proportionate way with the rights of local residents to the peaceful enjoyment of their possessions.

21. Entertainment events held to raise money for charity

21.1 Under the existing regime licensing authorities may waive or reduce fees for charitable events taking place outside Greater London.

21.2 Charitable events will not be exempt under the new regime because the risks associated with charity events where the aim is to raise money, albeit in a good cause, are no different to those at other types of public performances; for example charitable events, such as major concerts like Live Aid, do not give rise to any diminished risk to the safety of the public. It is perfectly sensible that the safety of the public is properly considered whether a concert is staged to raise money for a charity or conducted for profit.

21.3 The Secretary of State has powers under the Bill to set licensing fees and will be able to waive or reduce fees as she sees fit.

22. Licensing of live music in Scotland

22.1 It is often argued that the entertainment licensing that is used in Scotland should apply to England and Wales. Licensing law in Scotland has been separate to that of England and Wales for many years.

22.2 In general terms, the licensing system in Scotland provides that public entertainment is covered by a licence permitting the sale of alcohol, but only within formal permitted hours. Many licensed premises in Scotland do have extended licensing hours because of the more flexible system operating there. There is, however, nothing in the Licensing (Scotland) Act 1976 which denies the Licensing Board the power to restrict or forbid entertainment activities by conditions, either specified in by-laws or attached to licences. Although by-laws prohibiting live music in Scotland are rare, the law provides Boards with these powers should they be necessary. This is similar to the system proposed under the Bill whereby conditions would be attached to licences only where they prove necessary. As we intend to abolish permitted hours and the new hours, up to twenty-four hours a day, will be tailored to specific premises it would be inappropriate to adopt the Scottish system, which is based on national permitted hours. Our approach is more flexible.

22.3 Finally, the Licensing Bill sets out a system for licensing in England and Wales, not Scotland, and not any other country. Scotland is currently reviewing its licensing laws.

23. The new licensing regime and existing law

23.1 There are claims that that existing regulations relating to noise, fire and health and safety are sufficient and that entertainment should not therefore be licensed. There is however no law in this country, which addresses public nuisance generally.

23.2 It is also the case that in several respects, premises providing public entertainment are exempt from aspects of safety legislation precisely because the matters are dealt with by licensing law. Live performances raise issues of public safety and nuisance that must be addressed both to ensure the safety of those attending such events and the rights of local residents. But where these issues are not of concern due to the nature of the performance, costly conditions will not need to be attached to the licence.

24. Penalties for carrying out licensable activities without a licence

24.1 While it is true that performers who take part in a musical performance would potentially commit an offence if an appropriate authority under the Bill has not been granted, a defence of "due diligence" is provided in clause 137 of the Bill. This provides a defence against the criminal offence where "the act was due to a mistake, reliance on information given to him or to an act or omission by another person or to some other cause beyond his control, and he took all reasonable precautions and exercised all due diligence to avoid committing the offence". Accordingly, a musician should check that any venue has proper permission to stage regulated entertainment, but if he is misled by the organiser, he is fully protected by the Bill.

24.2 The penalties provided in the Licensing Bill are maximum penalties and, as with all offences, the courts would decide on the appropriate punishment depending on the facts of the case. Severe penalties might be appropriate in some cases, however rare, for instance where a musician put lives at risk by trailing bare cables through an audience.

DCMS January 2003

November 2002

The broad aims of the Licensing Bill are to be welcomed, of course. Deregulation of opening times is likely to reduce binge-drinking, and alcohol-related crime and disorder. However, if all the provisions of this otherwise liberalising Bill were enacted, this would represent the biggest increase in licensing control of live music for over 100 years:

The licensing rationale, where live music is concerned, is essentially to prevent overcrowding and noise nuisance. The government claims their reforms will usher in a licensing regime fit for the 21st century. But surely 21st century planning, safety, noise and crime and disorder legislation can deal effectively with most of the problems associated with live music?

Not according to Culture Minister Kim Howells. He says the swingeing increase in regulation is necessary because 'one musician with modern amplification can make more noise than three without'.

Of course it is true that amplification can make one musician louder than another playing without amplification. But that was true when the two performer exemption was introduced in 1961 and had been true for many years before that. The important question is: does live music present a serious problem for local authorities? Does it justify such an increase in control?

The answer is no. The Noise Abatement Society has confirmed that over 80% of noise complaints about pubs are caused by noisy people outside the premises. The remaining percentage is mostly down to noisy recorded music or noisy machinery.

In fact, while noisy bands can be a problem, complaints about live music are relatively rare. In any case, local authorities have powerful legislation to tackle noise breakout from premises.

All local authorities can seize noisy equipment, and they can serve anticipatory noise abatement notices.

Camden used a noise abatement notice to close the West End musical Umoja earlier this year. One resident's complaints were enough. And the police can close noisy pubs immediately for up to 24 hours. The trouble is, many complainants perceive the legislation as inadequate because their local authority doesn't enforce it effectively.

It looks as if musicians are being made the scapegoat for a problem that is nothing to do with live music. Certainly abolition of the two-performer licensing exemption will do nothing to reduce noise from people outside premises.

Rather late in the day, the Department for the Environment, Food and Rural Affairs (DEFRA) has just commissioned a study into the noise nuisance potential of the licensing reforms - but the study won't be completed until the Spring of 2003 at the earliest. A classic case of shutting the stable door...

The government says that standardising licensing fees, with no premium for entertainment, removes the disincentive to provide live music. This change is welcome. However, fees are only half the problem. The other half is the potential for unnecessary local authority licence conditions.

Earlier this year, Kim Howells warned the Musicians' Union that if it were to lobby for satellite tv to become a licensable entertainment, this would be 'resisted robustly' by the leisure industry. He did not say why, but the reasons are clear. The industry does not believe government assurances that local authorities will adhere to published guidance over future licence conditions. They fear the cost implications of conditions such as monitored safe capacities, and CCTV. (Two years ago the Home Office warned all local authorities not to impose disproportionate conditions. Few, if any, took notice).

Genuine 21st century reform for live music, particularly small-scale performance in pubs and bars, would see England and Wales brought into line with Scotland and Ireland, continental Europe.

Scotland is a good example because public safety and noise is regulated by UK-wide legislation. In that country a typical bar or pub can host live music automatically during permitted hours, provided the music is ancillary to the main business.

In New York City, premises of capacity 200 or less are likewise free of a requirement to seek prior authorisation for live music. Noise breakout is strictly monitored by street patrols.

In Germany, Finland and Denmark the provision of some live music is asssumed when the equivalent of an on-licence is granted.

In rural Ireland no permission is need for live music in a pub, and customers would think it very odd to suggest that it be a criminal offence unless first licensed.

The Musicians' Union has argued for reform along Scottish lines for some time. But the government has rejected this option. Our campaign for more live music, particularly in small venues, is supported by the Arts Council, the Church of England, Equity, the English Folk Dance and Song Society and many others.

The Union recognises that premises specialising in music, or music and dance (like nightclubs) need the additional controls that licensing provide.

But if live music of all kinds is to thrive in small community venues like pubs, an automatic permission, within certain parameters, is essential. We should not treat all musicians as potential criminals. That doesn't sit well with the participation and access agenda of the DCMS.

Hamish Birchall Musicians' Union adviser - public entertainment licensing reform

[Note Ed: The Musicians' Union has been so concerned about the Government's approach that they took legal advice from a QC this summer. He advised that the Government's approach is incompatible with the European Convention Article 10. They will be arguing that particular point in the coming weeks]

Parliamentary Adjournment Debate on the Music Industry June 12th 2002

Listen - They're Not Playing Our Tune

Pop is something we British are good at. We may not be able to make cars any more, or build ships. Or even equip our army with weapons that work. But when it comes to writing the songs that make the whole world sing, we've still got it. Even Tony Blair says so. "British pop music is back where it rightfully belongs - on top of the world", he proclaimed in a recent Foreign Office guide to the UK music industry.

But a talking point at this year's Ivor Novello Awards was the fact that in pop music we Brits are just not cutting it any more. The music industry bible Billboard revealed that week that there just four - yes, four - British singles in the American top 100. There was a time when British pop was a permanent presence in the upper reaches of the US chart, a time, even, when the Beatles hogged the top five positions themselves. And our highest presence in the album chart was that scruffy youngster Sting at number 38. Meanwhile in most of Europe British pop is fighting an increasingly tough battle with local repertoire and at home less than half our top twenty albums are British acts. What, exactly, has gone wrong?

A look at the nominations for this year's Ivors gives a clue. The UK's 'Best Contemporary Song' and 'Best Music and Lyrics' nominations consist of the likes of Robbie Williams' Strong and Madonna's Beautiful Stranger. Could our songwriting be part of the problem? Guy Fletcher - no mean songwriter himself - is the chairman of the British Academy of Composers and Songwriters, which organises the 'Ivors': "It is my belief that it is to do with our songwriting," says Fletcher. "There's still some good songwriting out there, but it doesn't always get to the right ears. The artists insists - or their managers or producers insist - that the songs come from within their own little clique."

Paradoxically, this is largely why so many pop songs are now co-writes. "Most co-writes nowadays take place only partially because they are creatively interesting," says Fletcher, "but also because they are commercially imperative: it's about keeping the song copyright within the business environment of the artist." In other words, the singer or the producer - or the manager - wants a share of the lucrative writing credit.

Multiple credits are also a marker of the enormous pressure writers are under to play safe to justify massive promotion spends. Like movie endings, songs get re-written and re-written until they're judged just right for whatever is the fleeting taste of the moment. But what this increasingly means in practice is that out go strangeness, harmonic invention and melodic adventure. In deference to the audience's minute attention span, out go musical structures which develop over 8, 16, 32 bars; in come two- and four-bar hooks. Out, too go story-telling, wit and metaphor in lyrics.

The point here is not the usual middle-aged bleat about how no one seems to write like Cole Porter any more. It is that the emphasis on the image, sound and sell of British pop is creating such a weak product that it is actually bad for business. For the public, easily duped in the short term, is surprisingly astute in the long term. Which is why we still discuss Abba records, but not, generally, those of their contemporaries Baccara or Smokie.

The pop industry, for all its hype and flash, is dependent on long term investment and long term returns, like any other industry. It has to pay for all the acts that didn't make it (at least nine out of ten) with the big-grossing, long-selling records known as 'catalogue'. And it just may be that your parents were right, and that good old-fashioned songwriting is the key to creating this kind of catalogue. Take the New Wave of the late 1970s, the anarchic musical uprising which was supposed to turn the industry upside down. Who were the survivors? The quality songwriters: Elvis Costello, Squeeze, Sting and precious few others.

A look at the summer's British album charts is instructive. Where are the British equivalents of Shania Twain and Santana - two albums each in the UK top twenty - or, for that matter Macy Gray and REM? And why are Engelbert Humperdink, Abba, The Moody Blues and Fleetwood Mac riding so high? Could it be that, faced with a dearth of great songs, people are simply turning to old catalogue? Much has been made of the technological threats to the music industry recently. But ultimately content is what will drive the industry, whatever the delivery system, and here the worm is already in the bud. Guy Fletcher: "World class song copyrights with longevity - those generally only come nowadays from the film writers. They're the only people who are in a position to write a great song, and get it recorded by somebody famous."

The breeding ground for writing talent is the least-known sector of the industry, the music publishers, who administer the copyrights of songs and nurture many talents before they get picked up by record companies. The publishers, at least, are aware of the need for stronger writers. Catherine Bell is General Manager of Chrysalis Publishing, who have signed talents like Moloko and David Gray: "We take a very long term view, and don't sign deals that are so unrealistic that if the album doesn't sell four million units we're not going to continue with them. We like to do a lot of development deals and work with the writers from the start and often we fund their first record release, but Chrysalis have always done more than the traditional publisher, and you need to do more these days."

Bell is adamant, too, about the value of a good song: "I think that people have forgotten how important the song is. People go on about producers and the recording artists, but without a song you have nothing. It doesn't matter if you have the latest remixer if you have nothing to remix."

Despite all this effort, one uncomfortable thought comes to mind. It's almost a heresy, but here goes. Maybe we Brits never were as good at pop as we like to think. When the Americans had Duke Ellington we had Henry Hall. In the era of Piaf and Marlene Dietrich, we fielded Gracie Fields and George Formby. We responded to Chuck Berry with Tommy Steele. Who was our Jacques Brel - Donovan? The Beatles were, of course, the glorious exception and some huge talents were launched onto the international market in their wake - Elton John, David Bowie, Led Zeppelin, Queen and so on. But perhaps what we are now seeing is a return to the pre-Beatles status quo, where this island specialises in quirky, throwaway music for itself.

Or maybe there really is serious talent out there, half-submerged in the tradition of Ewen McColl, Nick Drake, Richard Thompson and John Martyn, or germinating in bedsits and clubs outside the industry's reach. Tony Moore, manager of London's songwriting showcase the Kashmir Klub, has no doubts. "There's some great songwriting talent out there," he believes. "Definitely in the last two years I've seen a much higher level of quality of songwriting coming through the Kashmir Klub. I think there's a groundswell of people moving towards real songwriters instead of pre-packaged, production-driven artists. But it's going to take a while for that to filter through into record labels."

Moore agrees with the idea that Britain has to look hard at its songwriting if it wants to ride high in world pop again: "I think it's an enormous amount to do with the quality of songs. Historically, America's tended to support writers who have something to say, who don't necessarily say it in a brand new way but say it in a classic way. Britain has always been very preoccupied with image and fashion and we've become very focussed on our own market and forgotten what the rest of the world wants, what people want in the long term."

The prognosis may be bleak, but working at the grass roots has given Moore an unshakeable optimism: "There are some enormous talents who are unsigned: Rosie Brown, Jamie Lawson, a band called Must, the group Pixie Sixer, Catherine Porter. I'd sign them, if someone gave the money!" Is the music industry listening? If not, then the Prime Minister who invited our pop stars to No. 10 might be the one who saw them quietly slipping off the world's charts.

An edited version of the above article was published in The Independent on Sunday in May 2000 and is reproduced by permission. Alex Webb was at the time the Communications Manager of the MPA but wrote in a personal capacity. © Alex Webb 2000

WITHER MUSIC ON THE NET? by Peter Whitehead of the Bang Register

The Internet will totally change the music industry. Almost every functional component of the industry will migrate to the Internet. Most are already doing so. However, to take full advantage of new technology and the Internet it is important to adopt a cerebral approach to building the music industry for the 21st century. It is very easy to transplant an existing function onto the Internet (e.g. UK marketing in the form of a catalogue, soundbytes and an ordering mechanism). To a large extent this is missing the point. It works - it consolidates existing infrastructure and it is low-cost. But it leaves the field open to lateral and constructive thinking competitors to put in place creative infrastructures which eventually will take market share and need to be bought at a premium price - when the same ideas could have been developed in-house and put into practice at much lower cost.

I have defined the implementation of existing infrastructures on the Net 'stalagmites' and the creation of radical infrastructures as 'stalactites'. Both have functionality but the 'stalagmite' happens because the appropriate manager or director decides he or she wants to use the Internet to improve their existing operations - whilst the stalactite is implemented as a result of genuine creative thinking about how the Internet and digital technology can create new business and market share by way of e-commerce and new business models.

In the music industry this includes reaching out to Internet users, present and future, and saying 'if you like this, try this'. It is blatantly obvious that the existing record store is an archaic and inefficient way of introducing the public to new music. Older people tend to avoid record stores - maybe thinking they are too out of touch to know where to find good new music. And younger people have got used to being faced with a very limited array of 'product' - being largely what the major record companies are pushing that week and prepared to 'buy onto' the listening posts.

It really is shameful that in the music industry you cannot 'try before you buy' in a modern record shop - except the 0.1% or so that 'they' condescendingly offer you.

The new music industry will be consumer-driven. The customer will not put up with such a patronising and outdated attitude. In any other high street retail facility you can try out the item you want to buy. In the music industry you can look at it - if you're lucky. But looking is irrelevant. They've made CDs look alluring. Indeed the whole industry has 'gone visual' because it has realised that TV sells music.

Radio sells music too. But in the UK one or two key radio stations wield an unhealthy amount of power. Indeed the peoples' radio stations BBC Radio 1 and 2 are unregulated and have no 'Oftbeeb' to ensure that the music played is demographically representative of what the licence-payer is interested in hearing. This will change. The future of radio and TV is digital and interactive. And interactive means the consumer will be able to feed back selective information. In other words they will choose - to some extent - what they want to listen to according to what they already like.

This is earth shattering. It means we're heading for narrow-casting in place of broad-casting. Instead of having a million or more captive 'victims' subjected to an involuntary radio stream, smaller 'sets' of listeners will actually be able to listen to what they want to and maybe what they actually like. Modern radio is mass manipulation. You play what minimises channel hopping - psychological musical cannon fodder. What the punters want is 'if you like this, maybe you'll like this'. And once this is on offer, there'll be no going back. Market forces will mitigate against the current model of broadcasting. Advertisers will be able to buy a range of radio 'streams' enabling them to focus more accurately on their target audiences. Listeners will get a better deal. Pity the existing shareholders. There's no gain without pain - and radio equity will take a tumble before reaching new heights for those that grasp the new technology and use it properly.

So how will music in the future be sold if high street retail is failing us? Good question. Well, to start with, existing investments will be consolidated. The stores will (grudgingly) implement improvements. Most of these are pitiful. Booths to cut your own CDs (pick and mix). Wider listening facilities. Even Internet access and limited mail order facilities. It just isn't good enough. They should have embraced 'global listening' four or five years ago. Then maybe they might have clung onto market share. Why not allow buyers to listen to any track and buy or order according to availability. The technology was there. They preferred to make you buy what they wanted - not what you wanted. And now they're going to pay the price.

Music in the future will be sold in the form of artefacts (CDs, DVDs etc.), subscriptions, one-off transactions (streaming or downloads), and (eventually) microbilled play-on-demand. I shall also look at music for free.

ARTEFACTS

An example of new technology selling music artefacts is CDNow, Amazon and Boxman selling CDs by mail order. OK so it's still less than 1% of total industry turnover - but existing services give you limited 'try before you buy' and you have a degree of guidance as to what you might like. There is ample room for improvement and market share will continue to increase for several years - before dropping back as other ways of acquiring music become more attractive. And there's interactive TV and radio stations which allow you to respond with your keypad to 'spontaneous' musical promotions - i.e. special offers in the form of discounts on CDs.

The next development will be DVD audio and formats which allow audio, video and multiple channel audio so you can make your own mixes and add your own tracks (DIY karaoke).

And there will be a boom in mail order through sales in public places where the licensing of recorded music (e.g. in pubs, clubs, hotels, trains) will be conditional on having information displays giving artist, track, CD together with an instant ordering facility via mobile phone or debit card.

SUBSCRIPTIONS

Nobody is quite sure how subscriptions will work. The idea is that you select a subscription that suits your needs and what you can afford - and you have the right to listen to and/or download a whole range of existing and new music. The problem is how to distribute the money fairly - and how it can be done to incentivise the best new music to come through. I suspect that this mechanism will favour established artists and tend to allow the 'majors' to keep a grip on their market share. Therefore it will mitigate against new artists - where the user will have pay for their choices artist by artist in order to exercise their 'voting' right as to who should succeed and who should fail. Fortunately for new artists they have a tremendous advantage on the Internet as they can make their music available free whilst they are building their fanbase. However this depends on selection mechanisms for music on the Internet being far more effective than they are at the moment. Don't worry. Great new mechanisms are on the way - I am involved with several.

To get a better idea of how subscription services to music on the Net and interactive TV will work consider the model already in place in the film industry: According to how keen you are to see or own a film you can contribute to the film's revenue stream according to a list of chronological opportunities: